This past week an older friend of mine (let's call her Adrian) reached me by phone when she was in a depressed mood. Her life wasn't working well (and hadn't been for quite a while). Near tears she asked me for a date to help her walk through whether or not to commit suicide. Oh boy. I agreed to be there for her (how would it have landed if I'd turned her down?), yet I was shaken and unsure how to proceed.

My emotions and thoughts were all over the place:

—I was sad that Adrian has had such an unhappy life.

—I was immediately touched by a sense of loss (pre-grieving?). I didn't want to lose my friend.

—I felt guilty that I hadn't initiated more contact with her the last few months.

—I was flattered that Adrian felt I could handle such a sensitive and weighty assignment. She knew I didn't have a moral judgment about suicide, and she knew that I wouldn't freak out. She knew I'd take her seriously and help her explore her options dispassionately (isn't that what good friends do?).

—I was intrigued. It's a powerful topic, though one I'd never focused on before, beyond the moral and existential questions. How would one make this decision? It turns out I have a number of thoughts about it, and I was glad to have time to prepare.

—In addition to all of the above, Adrian's situation offers an insight into what it's like to be on the gray side of 70 in these days of Covid. For anyone in that age range, there are much higher odds that you'll die from a Covid infection than for younger population segments—the death rate is 8% for those in their 70s; 14% for those 80+; and only 0.4% for those under 50. Of course, those are just averages. If you're immunocompromised (as Adrian and I are) the odds are significantly worse.

[Digesting these statistics helps explain some of the tension we're witnessing between younger people who are impatient to resume normal life and seniors who are more cautious—those two age brackets are looking at different odds. What fascinates me the most is the fierce determination among some in the lower-risk age range who insist on their right to decide for themselves how safe it will be for others. I don't have any problem with individuals making choices for themselves, but that's not the world we live in—especially when a quarter or more of those infected with Covid are asymptomatic.

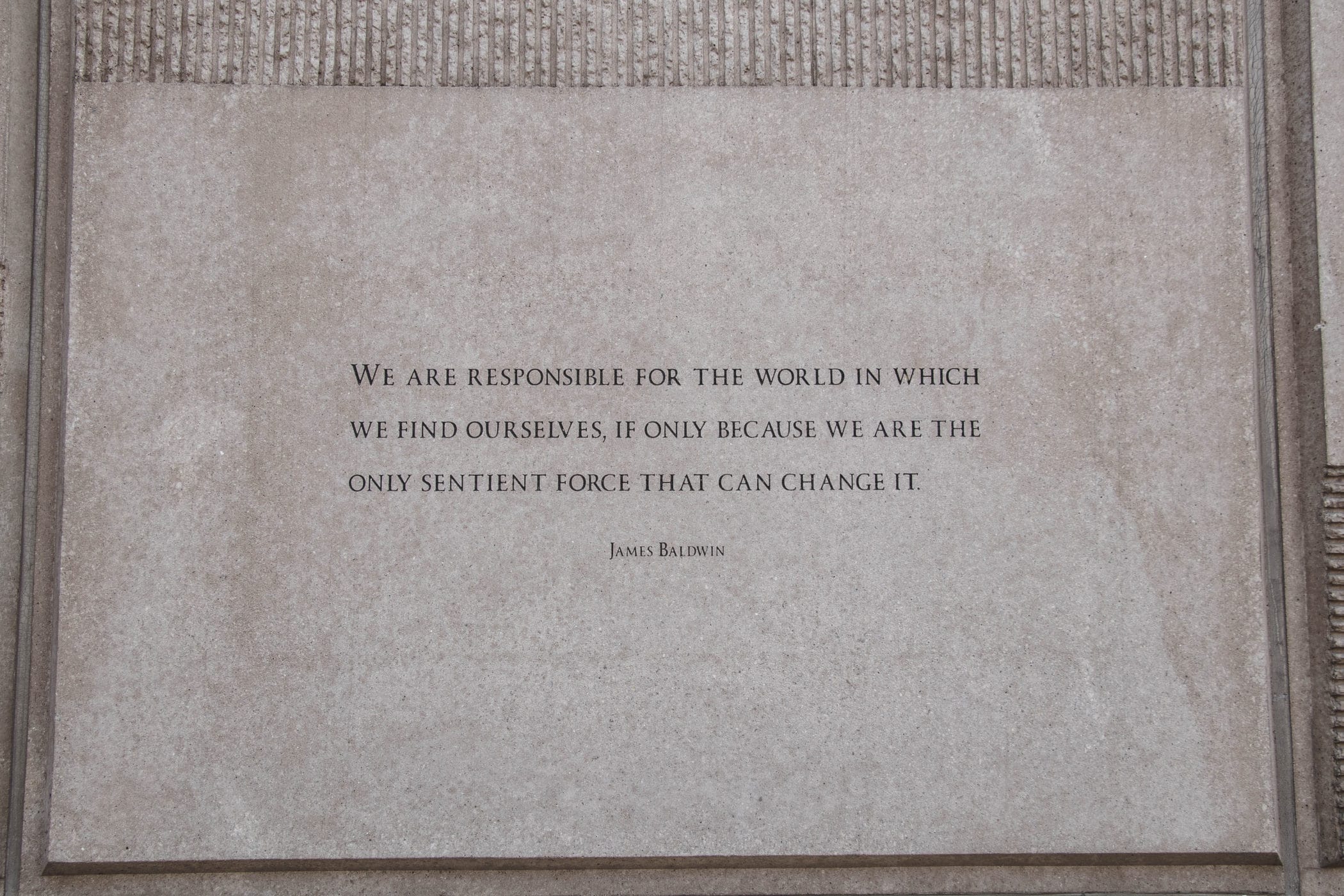

When people defy the advice of health care professionals by not wearing masks or maintaining social distancing, they are essentially saying that they get to be the sole arbiters of what's acceptable risk for everyone around them. In consequence, those who feel that more cautious public behavior is called for need to be mindful of the presence of those who don't care to take their concerns into account.

Thus people who believe themselves to be at risk need to be extra cautious about being out in public, because they cannot rely on others being mindful of their situation. How did we get to be so uncaring?]

In any event, Adrian and I are both in the better-wait-for-a-vaccine-before-going-to-a-restaurant category, which reinforces isolation for our age cohort—and this is on top of the struggles that seniors ordinarily experience trying get enough human contact to sustain health. Our culture is youth oriented and we tend to warehouse or otherwise set aside our seniors—not because we no longer care about them or they can no longer contribute, but because younger folks don't want to be burdened by elder care, are impatient for their time in the sun, and prefer to learn through doing it themselves than by being mentored. When you add into the mix the mobility of contemporary society, to the point where adult children often live at some distance from their parents, it's tough on seniors.

All of which is to say it can be lonely growing old, especially for those without a partner, and the pandemic has made it worse. Susan and I are highly fortunate to have each other, as well as the surrounding neighborhood, where Susan has gradually built a wealth of caring relationships over the course of four decades. We are not at all as isolated as Adrian.

Our next door neighbor—in her 80s—had been living alone for some time and recently fell and broke her hip. On top of that she has been suffering memory loss (onset dementia?), and her four adult children collectively decided that it's time for mom to move to an assisted living facility. On the one hand this makes total sense. On the other, it's hard on our neighbor to make the adjustment, losing the anchoring familiarity of her home of 50 years. It's a sad time.

Although Adrian has retained her independent living, she is in a housing complex of 400 where no one really knows her. While everyone needs caring relationships in their life, not everyone has it. And that's brutal.

Against this backdrop, I want to share my thinking about Adrian's choice about whether to stay or go. First I turned my attention to what I know about her situation:

Factors

• She has been in poor health for many years.

• Adrian has weight and mobility issues which make it hard for her to get around (even if it were safe to do so).

• She lives in a large housing complex in an urban setting and has no friends in that location.

• She has a car and still drives (though she's nervous about going out because of the pandemic).

• She can hire support for cleaning and shopping, but it doesn't provide companionship.

• It's been hard for her to avoid feeling overwhelmed by the chaos and disorganization in her life, and then she falls into a pattern of self-deprecation at the end of the day if she hasn't accomplished much. She finds it difficult to make a plan and to stick to it.

• One of the most depressing things for Adrian is that she doesn't feel that she's being much use to anyone these days—there is no demand for what she has to offer.

• She has one sibling, with whom she has a complicated relationship. Her sister lives in a different time zone and doesn't provide much emotional support. She has no other living family—though she does have a wealth of friends sprinkled across the continent.

• Because she has an extensive background in community living, the lack of social contact in her life today is all the more glaring.

• Electronic connections are helpful (phone, email, social media), but are not the same as being in the same room.

Next I elucidated the questions I would use to explore the possibilities.

Questions

1. How do you assess the balance of joy and satisfaction relative to pain and misery in your life right now? (While I can't imagine this will look good—else why be thinking about suicide—how bad is it? Let's lay it out.)

2. What are your prospects for turning this around? Can you reasonably expect things to get better? Are there things you can do that will make a difference? What help do you need, if any, to move things in a positive direction? Be specific.

3. Is there work (or projects) that would inspire you to stay alive to do?

4. Is there a role for me to play in reinforcing the positive answers to the prior two questions?

5. If you decide in favor of suicide, walk me through how you'd do it. Do you have the will to carry this out?

6. If you decide on suicide, what do you need to complete or get in order first (for example, are there estate decisions to make)? Walk me through the timeline. Is there a role I can play in this?

7. Who do you want to say goodbye to?

Meanwhile, I am mindful that I can support my friend (and contradict the story that no one cares) by the simple act of initiating phone calls once every fortnight or so. And if the impetus to discuss suicide surfaces again, I'll be ready.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us