When asked by a foreign journalist about the Negro problem in America, author James Baldwin replied—in the '60s mind you, more than 50 years ago—"We don't have a Negro problem in America. We have a white problem."

• • •

Racism Rises to the Top

Racism is on my mind a lot these days. It's been the first thing to come along in months that's knocked the pandemic off the front page—of both the media and my consciousness.

Two weeks ago, George Floyd was murdered by a white Minneapolis police officer who had a knee on his neck for over eight minutes while George was handcuffed and prone on the ground. The incident happened in broad daylight and was captured on video camera by onlookers who were horrified at what was happening. There were three other police officers present and none tried to intervene as George begged for his life and stopped breathing. George had been detained as a suspect in passing a counterfeit $20 bill. He was unarmed and did not resist arrest.

Ahmaud Arbery, a 25-year old unarmed Black man was killed Feb 23 while jogging in daylight hours in a residential neighborhood (part of his usual running route) in suburban Brunswick GA. The shooters and pickup owners were Gregory McMichael (64) and his son Travis (34). Although the incident was caught in video camera, the McMichaels were not arrested until May 7—a shocking 74 days after the killing.

Last Friday would have been the 27th birthday of Breonna Taylor, a Black emergency medical technician, but she was shot to death March 13 by Louisville police officers executing a no-knock warrant, searching for a suspect in a pre-dawn drug raid gone bad. She was asleep in her bed at the time, and was shot eight times. Police were looking for a suspect already in custody.

Amy Cooper, a 41-year-old white woman, made up a story when phoning police about a 47-year-old Black man (Christian Cooper, no relation) attacking her and threatening her life when all he had done was asked her to leash her dog in Central Park May 25—the same day George Floyd was choked out in South Minneapolis. While the preposterousness of the woman's claim was exposed immediately, it's outrageous that she thought she could get away with it.

• • •

The Institutional Dimension

As awful as these incidents are, the greater horror is that it is only a sampling of the latest in a very long line of violence and injustice of whites towards people of color—in this country that proclaims itself the land of the free, without any apparent sense of irony.

How far does this go back? All the way. The original US Constitution (1787) specified that only white men who owned property had the right to vote. Despite incremental changes over the years that have extended the vote to all US citizens (notably the Emancipation Proclamation of 1963; the 14th and 15th amendments to the Constitution following the Civil War; the 19th amendment guaranteeing women's suffrage in 1920; and the Voting Rights Act of 1965), racism is bred in the bone, and is so ingrained in American culture that it goes largely unnoticed by whites—the segment of the population for whom the deck is stacked. (In fact, this pernicious injustice exists everywhere on earth that whites have settled, though I will focus here only on US culture, the one I know best.)

It is directly related to why people of color are more apt to get infected by the coronavirus and to die from it. People of color are less likely to get hired for good jobs, they get paid less for doing the same work, they are more likely to get fired in hard times, they have less access to good schools, they have less access to entrepreneurial capital, and they are subject to being more targeted by police whenever they go out. All of this adds up to more stress and less income, which translates into poorer health, reducing the likelihood of their surviving being infected by Covid-19. It's a vicious circle.

While George Floyd's killing was no more heinous or inexcusable than many other atrocities of whites toward people of color, it has turned out to be a flashpoint with respect to racism. Eighteen days later, the protests have become international and are gaining momentum even as I type. Importantly, the concept of systemic racism is now on the table—that thing that James Baldwin was speaking of in my opening quote. It's about time.

On the one hand, it’s gut wrenching to have this shoved in our face. On the other, maybe—just maybe—it will wake whites to our need to insist that institutional racism be dismantled. On the hopeful side, there has never been as much white attention to this issue as there is now, and it will absolutely take a major shift in white consciousness to address this in a serious way. People have to demand it. In that way, the protests are wonderful, and it’s heartening to see how widespread they are.

On the cynical side, why will it be different this time? Can we trust the political process to do the work? Politicians are too focused on getting elected and have the attention span of a sunfish. In all of the ways that President Trump has disgusted me—and there are many—his current emphasis on law and order completely misses the mark and repulses me the most. Fortunately, even the lock-step Republicans are starting to push back on his misplaced focus on a military response to suppress looting and burning. While real things, they are a distraction from the main issue.

Biden is saying the right things, yet what will he actually do? If he gets it, why wasn’t he more active in this arena as VP for eight years under Obama? Police violence is a symptom and there is work to do there, but that’s derivative from whites who have been stubbornly comfortable with their privilege and oblivious to looking at it.

We need a sea change. Time will tell whether we get one, or just another high tide of outrage.

• • •

My Journey

There is a lot of work to do, some of which needs to be done by me. As I've come to a growing realization of the dimensions of racism, a large question looms over me: what should I be doing (that I have not been doing already) as someone who wants to be part of the solution?

I'm in anguish over this. My life has been bathed in privilege all along and it has taken me my entire 70 years to get to the degree of awareness that I've now achieved—which is only a point on a journey; I don't expect to ever complete the peeling of this onion. While I'm not particularly proud of that pace, here I am.

So this is a status report on what's bubbled up for me this last month. Disclaimer: my journey is just that—my journey. Writing about it helps clarify my learnings and the road ahead. If it's inspirational for my readers, that's great, but it's wholly up to each of you to make your own assessments and to make your own decisions. I do not presume that my path should be yours.

—The first step I took was to accept an invitation in early May from my good friend María Silvia to participate in a white racism study group—12-15 of us meet (via Zoom) for an hour weekly to wrestle with this issue, using Robin Diangelo's White Fragility as an inspirational point of departure. It helps to explore this compelling, yet tender topic with fellow travelers. We stumble along together.

—I've committed to educating myself about the dimensions of the problem (see more on this below).

—I am trying to learn to see what I've been conditioned to not notice. The trick here, of course, is that you never know when you're done. Maybe you never are.

—Can I commit to objecting to microaggressions as I encounter them? There is definitely the need, yet I am constantly wrestling with finding a way to do so that has a chance of being constructive. I am frequently up against defensiveness and denial, but maybe I should speak up anyway. This is hard. The divisiveness in the current political climate makes me sick and I desperately don't want to be fomenting confrontation. Yet I also don't want to be ducking the work, and complicit in the continuation of white racism. Argh!

• • •

The Minnesota Story (not so nice)

Minnesotans pride themselves on being civil (Minnesota nice) and generally progressive. As a citizen here since 2016 I figured I should familiarize myself with my adopted state's history with racism. Unfortunately, it's embarrassing. While we like to brand ourselves as the bastion of forward thinking in the Midwest, our history with respect to racism tells a different story. Let me lay out three atrocities that frame the picture:

—As noted above George Floyd was murdered by members of the Minneapolis police force, in a blatant display of unnecessary force by a white officer. Worse, this is not an isolated example. There have been unaddressed complaints about the Minneapolis police for years.

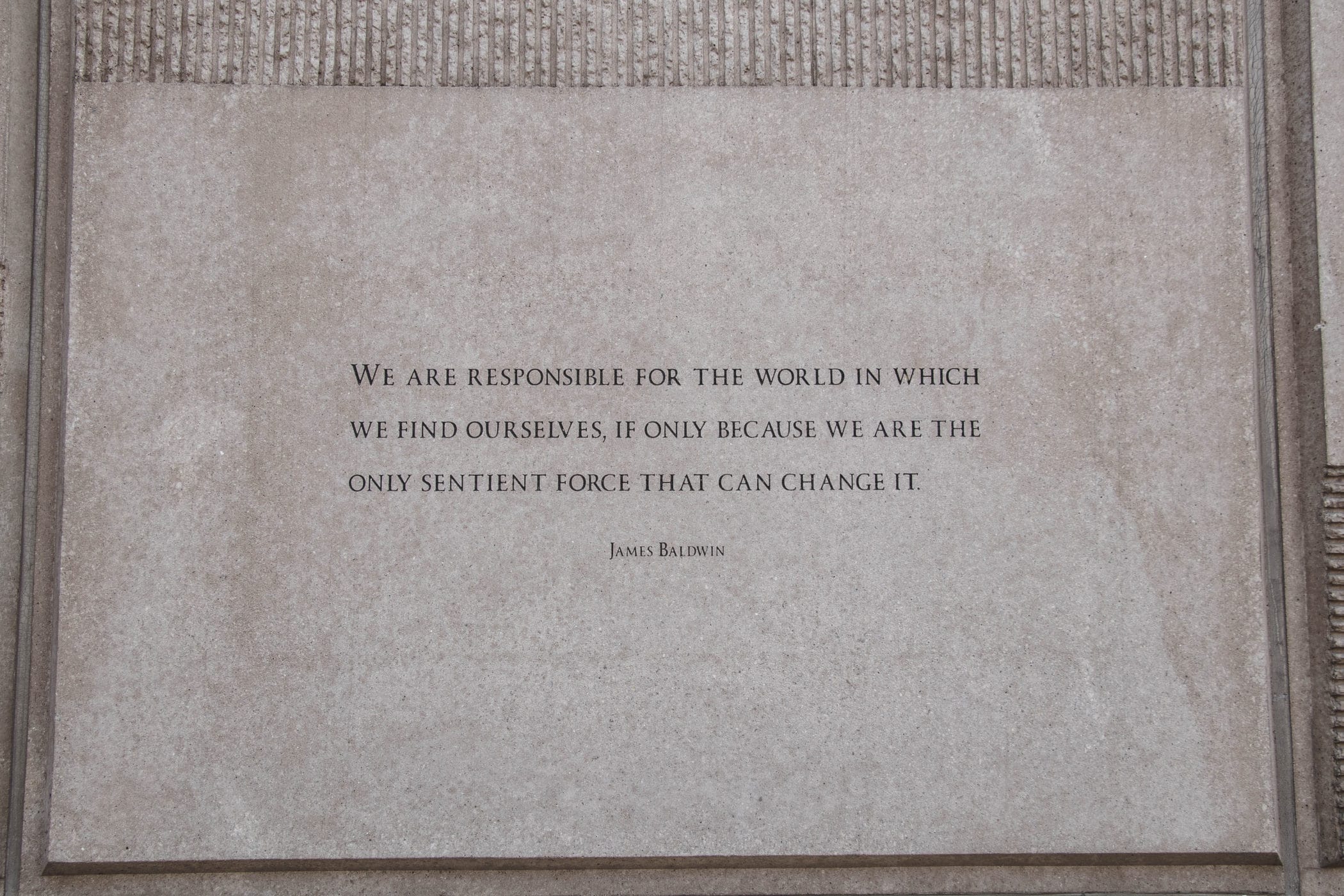

—Next Monday will mark the centenary of the lynching of three Black itinerant circus workers—Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson, and Isaac McGhie—at the hands of a white mob in downtown Duluth, incensed by the spurious claims of their having mistreated a white couple. The photo image at the top of this post is of a portion of the memorial of this racist tragedy at the location where it occurred, at the intersection of East 1st St and North 2nd Ave. Michael Fedo's The Lynchings in Duluth tells the story without embellishment.

—Back in December, 1862, the largest mass execution in the nation's history occurred in Mankato, when 38 Dakota Sioux were hanged en masse. The Native American tribe was frustrated with the US government's reneging on treaty promises, systematically destroying the habitat on which the tribe depended for food, and delaying annuity payments specified in treaties. Things came to a head in the summer of 1862, when, in desperation, the Dakota Sioux asked Andrew Myrick, the chief government trader for Minnesota to sell them food on credit. His response was said to be, So far as I am concerned, if they are hungry let them eat grass or their own dung. The Dakota Uprising ensued.

They killed settlers in the Minnesota River Valley, in a desperate attempt to drive them from the area. The US Army quickly quelled the violence, interning more than 1000 in the process—women, children, and elderly men in addition to warriors. A military tribunal sentenced 303 of the warriors to death. Though President Lincoln commuted the sentence of 265 at the last moment, the remaining 38 were executed. The following spring the remnants of the Dakota Sioux were summarily expelled from Minnesota.

All of which is to say, I need not stray far from home to find work. Racism is all around and deeply rooted. As cartoonist Walt Kelley had Pogo Possum say (in support of the first Earth Day) in 1970, pointing out succinctly who bears responsibility for worldwide pollution), We have met the enemy, and he is us. It is no less true of racism.

I will close with something inspirational and pithy from James Baldwin, chiseled into a panel of the Jackson, Clayton, McGhie memorial:

No comments:

Post a Comment